escort şişli nişantaşı escort bayan mecidiyeköy escort hulya şişli escort duru mecidiyeköy escort meltem mecidiyeköy escort defne mecidiyeköy escort yaren mecidiyeköy escort deniz escort bayan mecidiyeköy escort ferda mecidiyeköy şişli escort pelin vip escort sınırsız escort grup escort mecidiyeköy escort sıla mecidiyeköy escort ezgi escort istanbul

Information

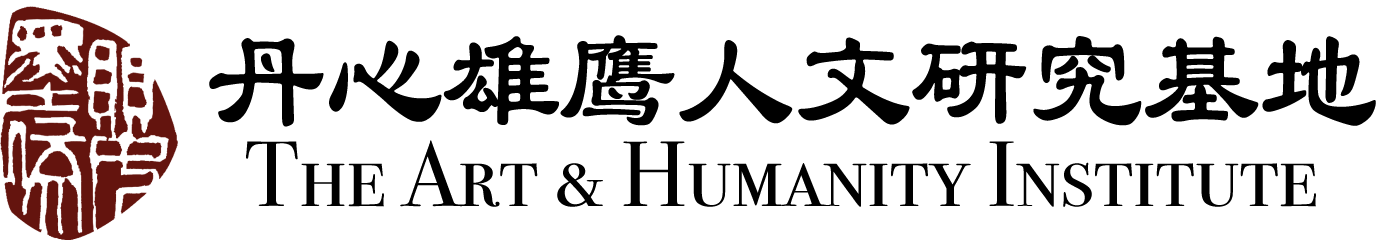

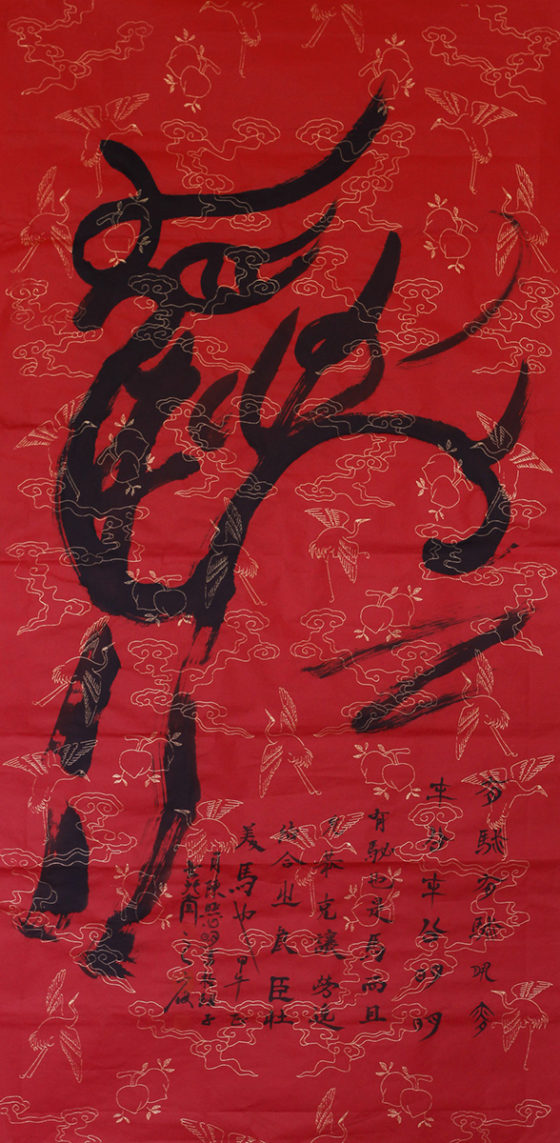

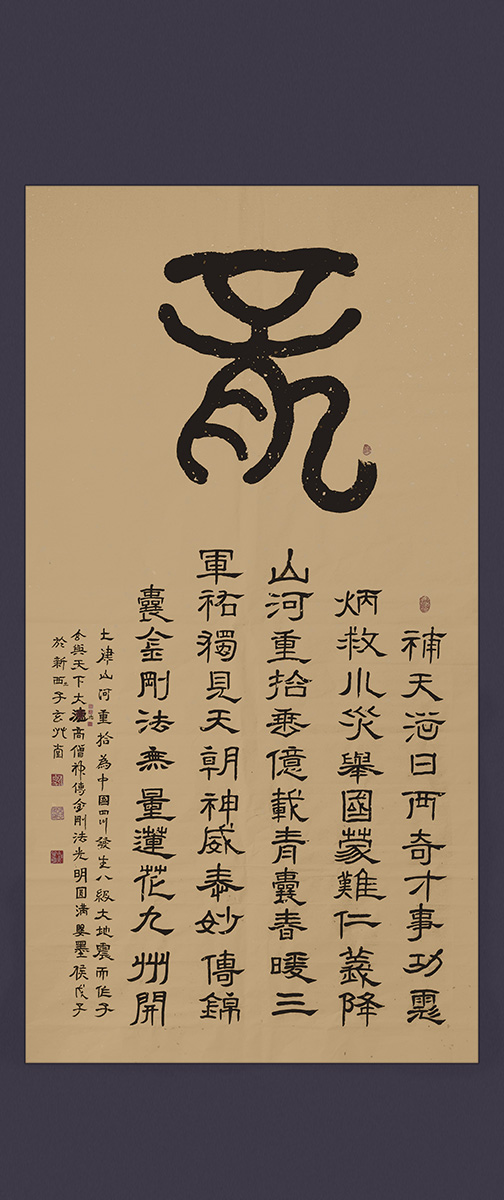

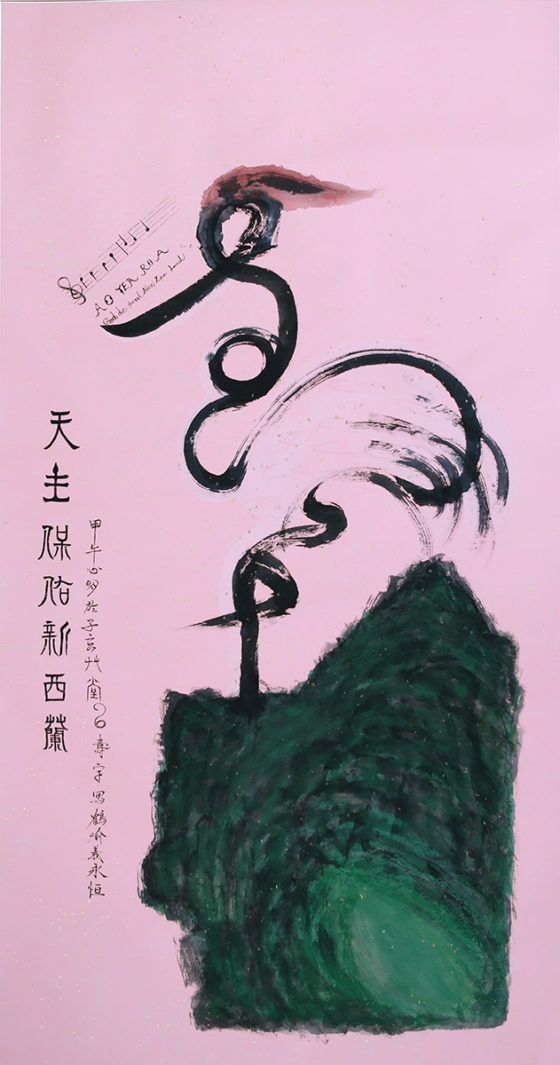

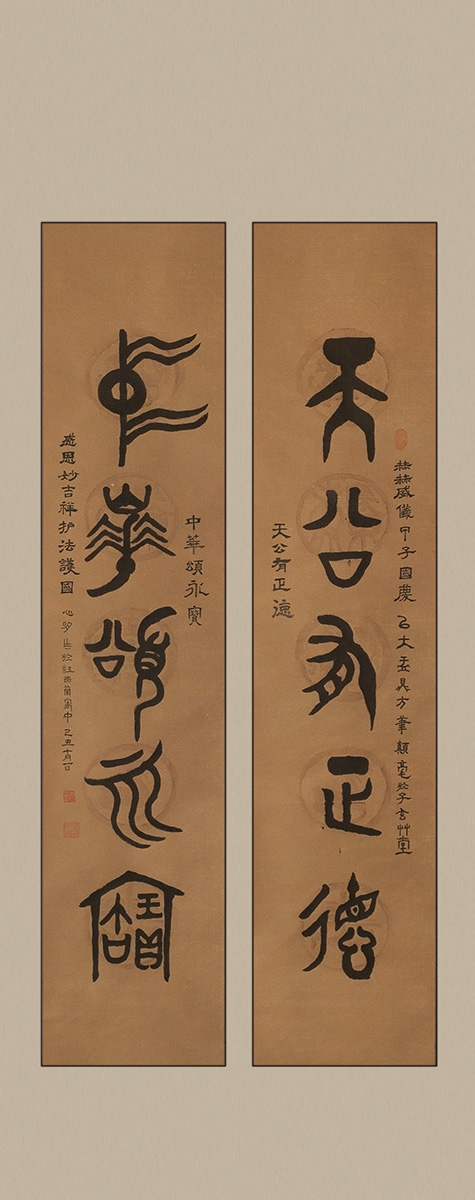

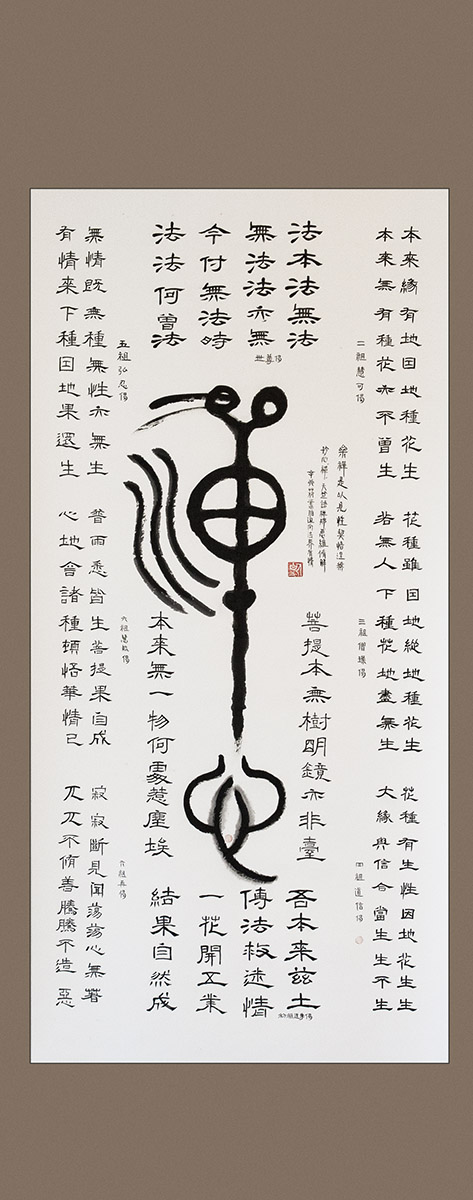

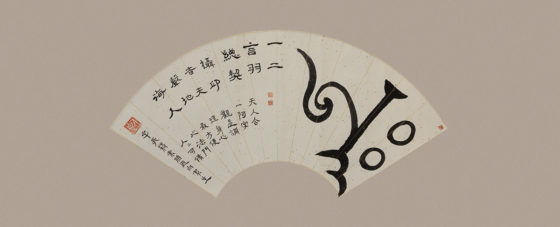

For the year of horse- Hanging Scroll 176x64cm

《得道马》 由“有駜” 二字组成

问世间谁识“得道马”?

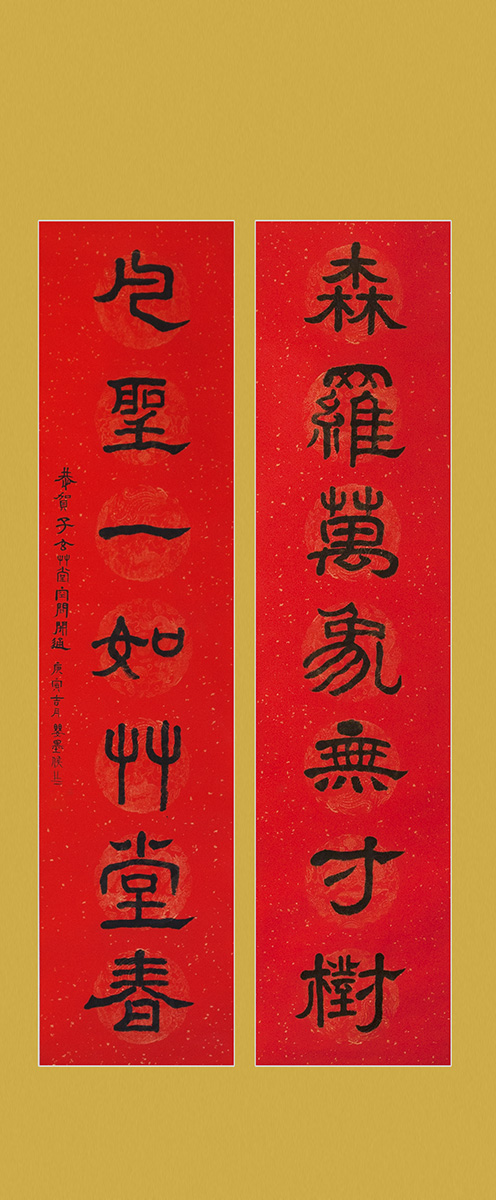

中国人自古以来,每逢佳节,必有两种文化的“应节”:

子玄草堂贺岁“应节”,世界各地亲朋好友、

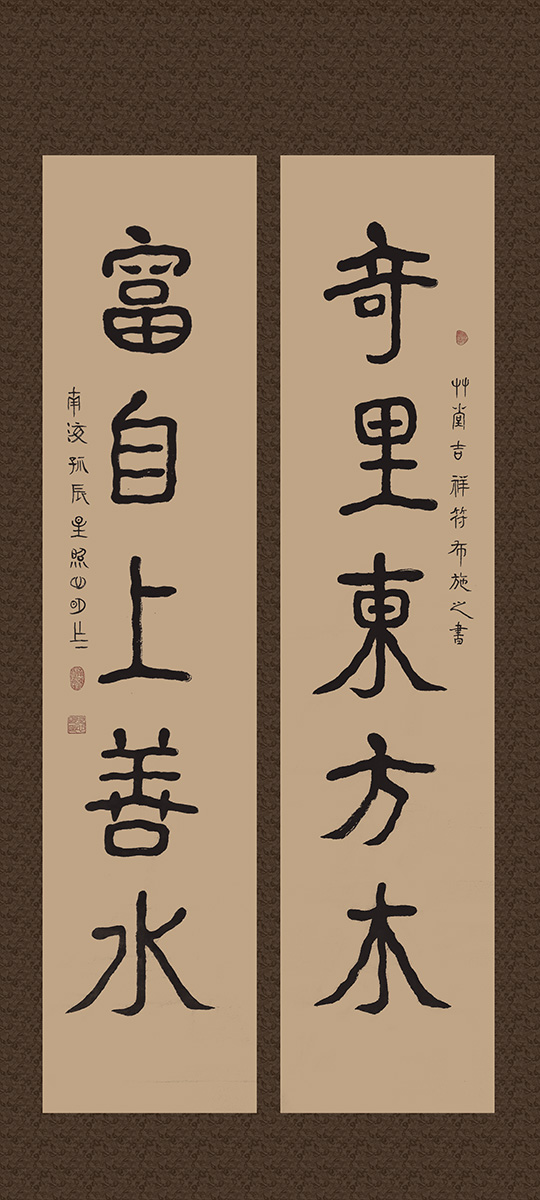

甲午马年(2014年)与往常一样心明写完了满桌子的 “索书”,书生意气,不能脱俗。

“充斥传媒的都是千篇一律贺岁制作,

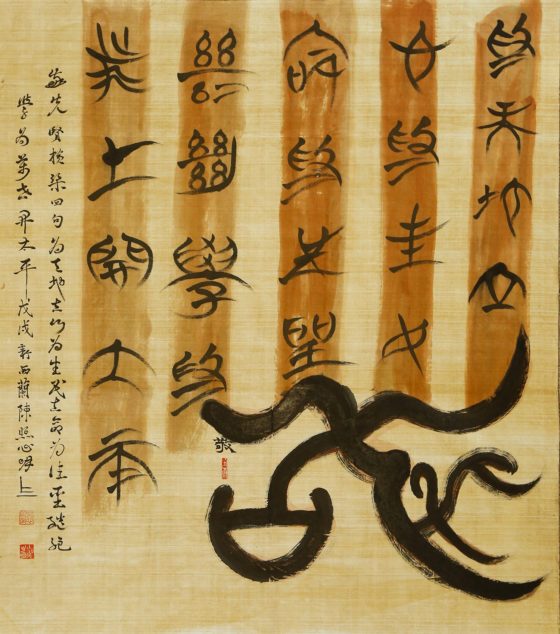

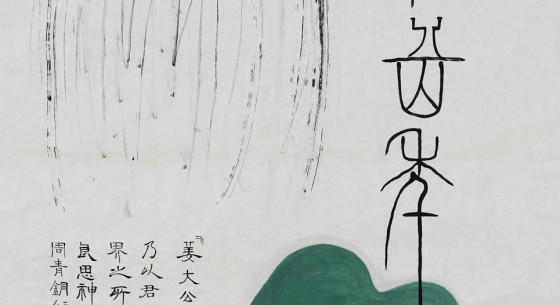

又一次以中国书法特有的宇宙螺旋气场符号心手双畅。

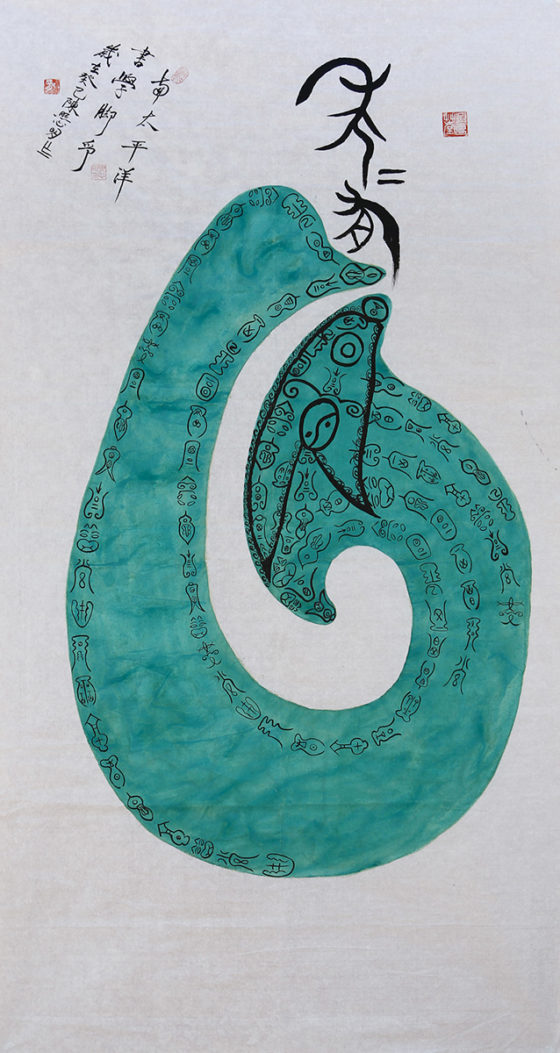

这不就是一匹“得道马”!子玄惊喜地给作品命名。正所谓:

The “Attained Horse” takes shape from the two characters “有” (own) and “駜”(strong horse)

Who in the world can truly know the Attained Horse?

Since ancient times, whenever festivals came around, the Chinese always followed two currents of celebration. One is the hearty “culinary culture” of the people—families savouring abundant reunion feasts. The other is a “culture of ritual and music” cherished by the literati—poetry and calligraphy, zithers and chess, histories, wine, and flowers. Flowing on for millennia, these twin cultural streams remain unbroken—hence Li Xueqin’s words: “Among all original civilizations with their own independent roots, Chinese civilization alone endures unbroken to this day.” (from his work Studies on Three Generations of Civilisations)

Here at Zixuan’s Hut, in honour of the New Year, friends and students worldwide yearn for the “auspicious calligraphic symbols” penned in these halls.

During the Jiawu Year of the Horse (the year of 2014), as usual, Xinming answered myriad requests for calligraphy—his scholarly spirit aflame, yet unable to escape the mundane tide.

“Everything in the mass media is a tired echo of seasonal greetings,” Zixuan admonished. “With your learning and your mastery of symbolic writing, you ought to stun the world!” These words sparked in Xinming’s mind a vision from the Book of Songs, “Lu Song”:

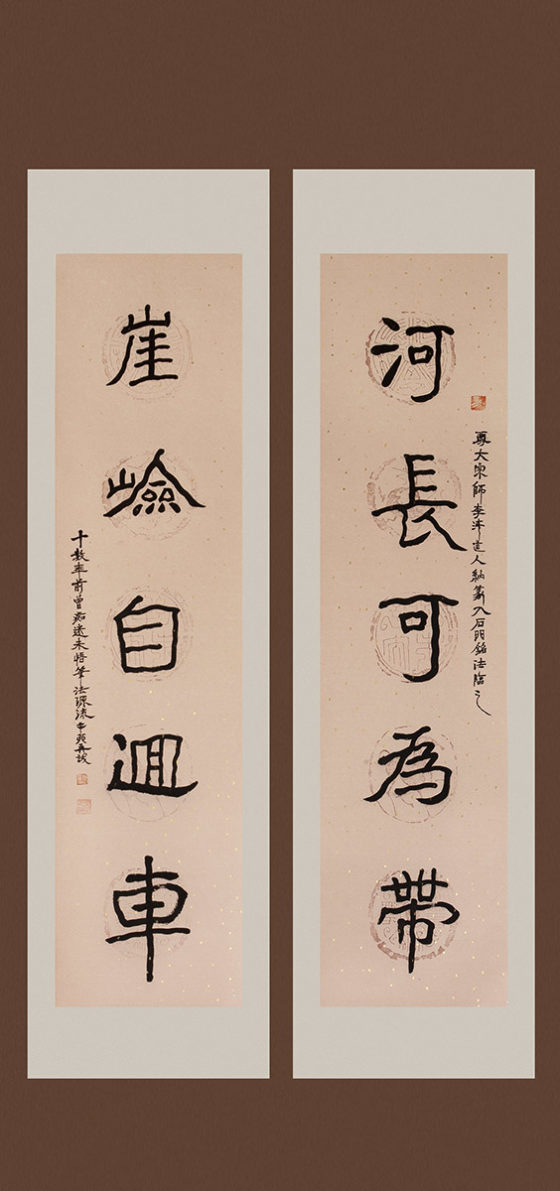

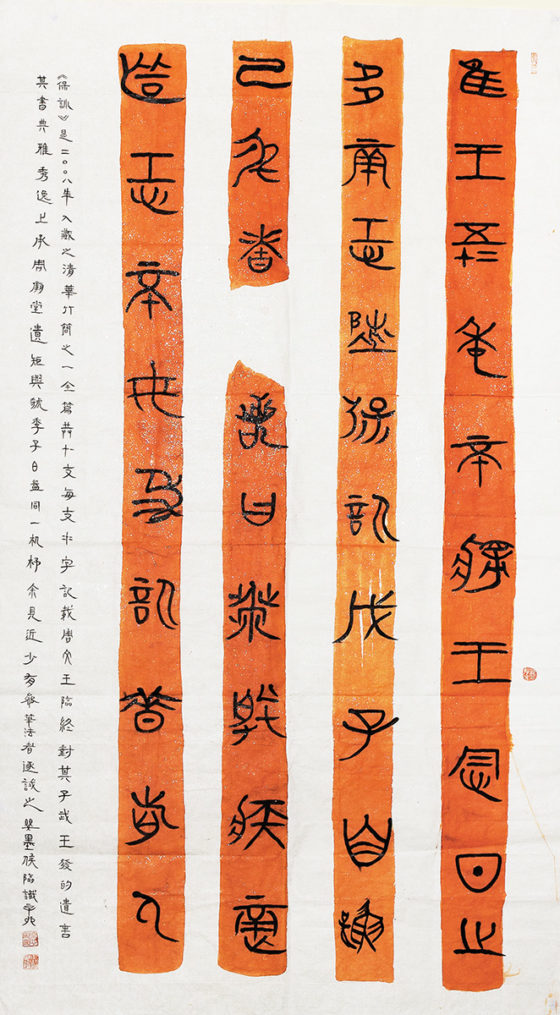

有駜,有駜有駜, Strong horses, majestic and sturdy,

夙夜在公,在公明明…Toil day and night, diligent and thorough…

This verse portrays the Duke of Zhou in all his dignified virtue, respectful in bearing, conscientious in duty, and loyal to the people. “有駜” indeed refers to a horse, one that balances hard work with rest, reaps achievements yet remains humble: a noble steed in its glorious prime. Who in this world can recognise the Duke’s benevolence?

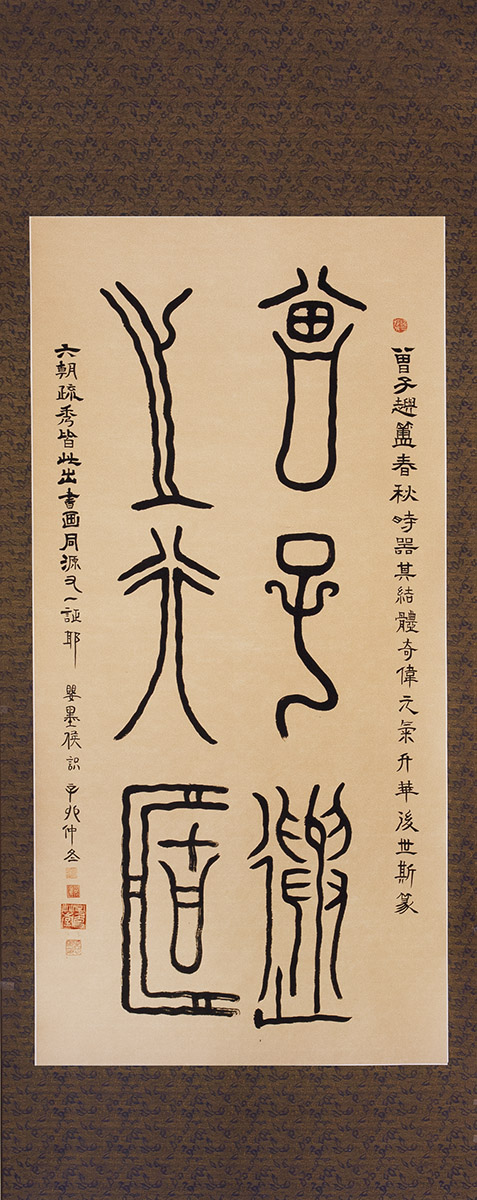

Thus, Xinming chose to fuse seal script into the simpler form “纳篆入简” (Take the qi of Zhuan style into Bamboo stripe carving style). From the ancient San Shi Pan’s rendition of “有”, she sketched the horse’s spirited eye. With a vigorous cursive for “駜”, she conjured the vision of a celestial horse charging across the heavens. In shaping the forelegs, she played with brushstrokes of emptiness and solidity, creating a rhythmic reveal of muscles and sinews beneath that majestic form. The final two strokes breathed life into the steed’s tireless gallop from dawn till dusk, leaving behind a trail of wind as it came to a graceful halt.

Once again, she revelled in the unique cosmic spirals of Chinese calligraphy, a dance of mind and hand as one. Su Dongpo once said, “He who paints merely for likeness in shape, paints like a child.”

And there it stood, a vision of the “Attained Horse.” Overjoyed, Zixuan named the work thus. Truly, we may ask:

Who in this world discerns this Attained Horse? Burdened with honours and benevolence, it shall stand in history forever.