escort şişli nişantaşı escort bayan mecidiyeköy escort hulya şişli escort duru mecidiyeköy escort meltem mecidiyeköy escort defne mecidiyeköy escort yaren mecidiyeköy escort deniz escort bayan mecidiyeköy escort ferda mecidiyeköy şişli escort pelin vip escort sınırsız escort grup escort mecidiyeköy escort sıla mecidiyeköy escort ezgi escort istanbul

Information

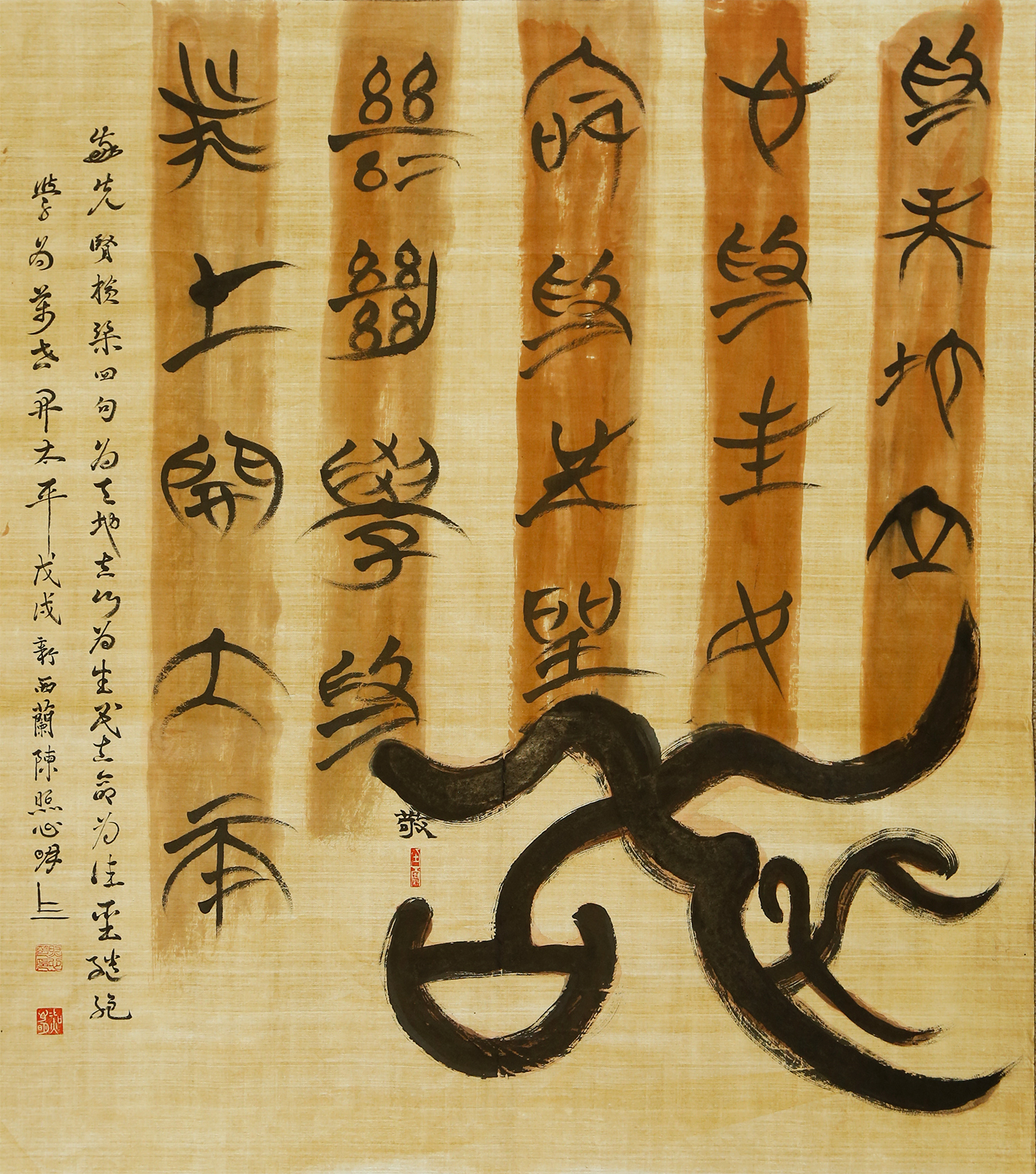

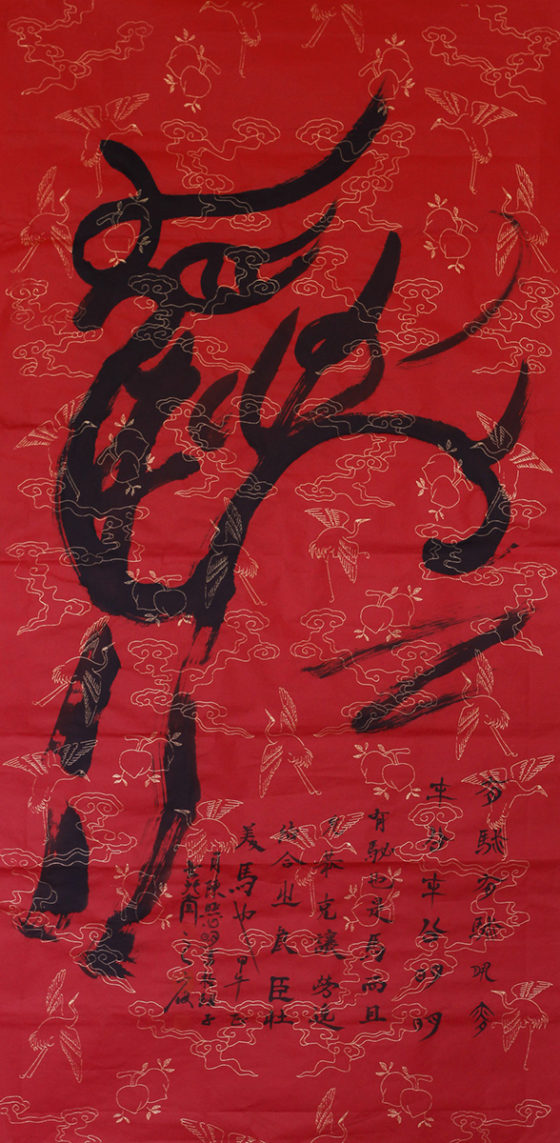

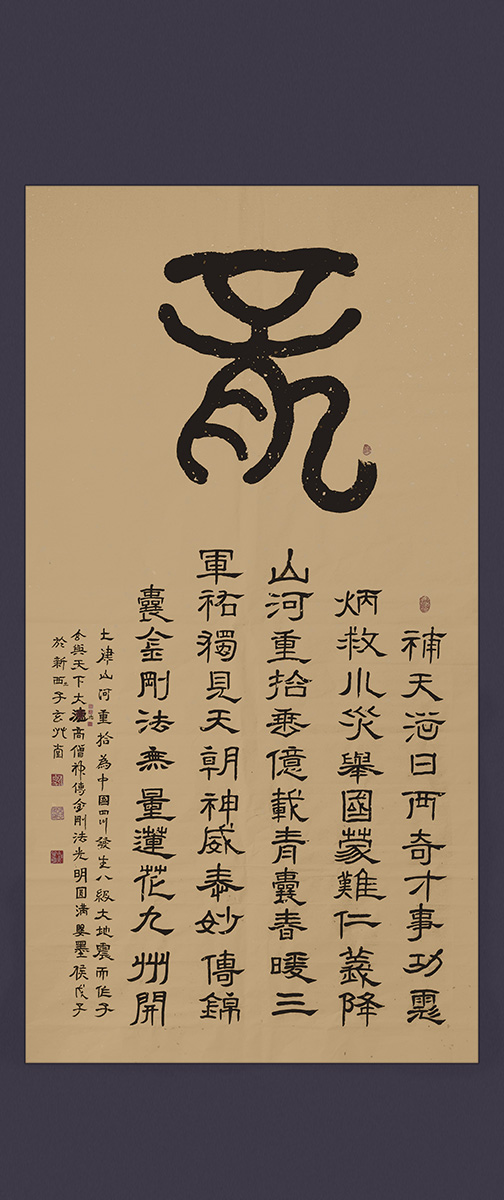

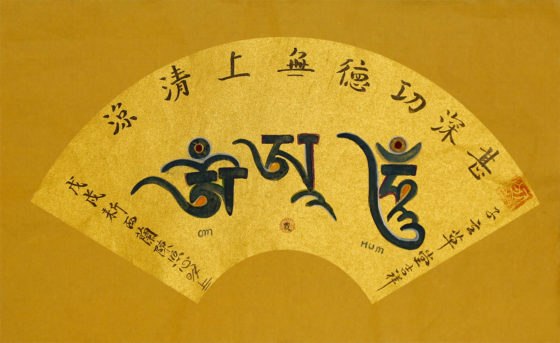

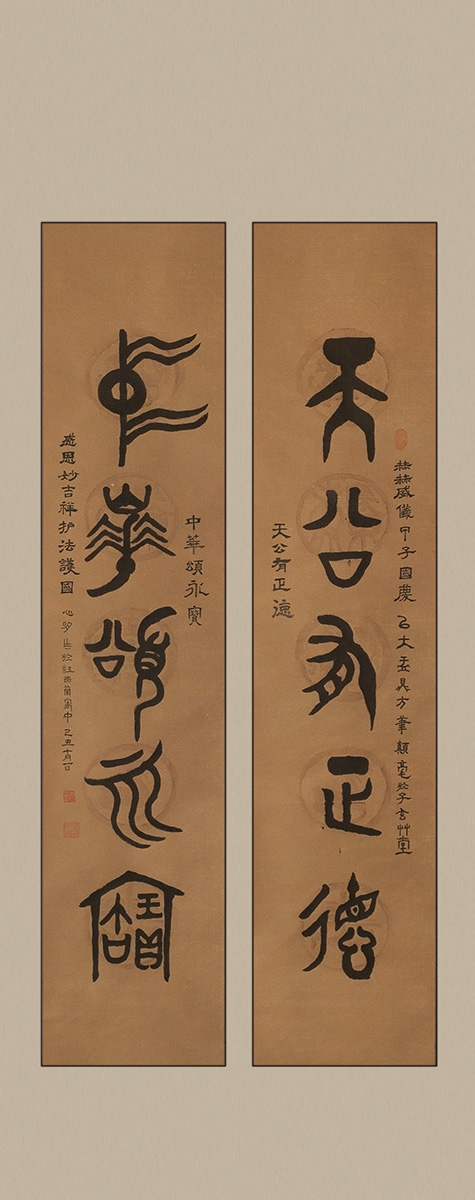

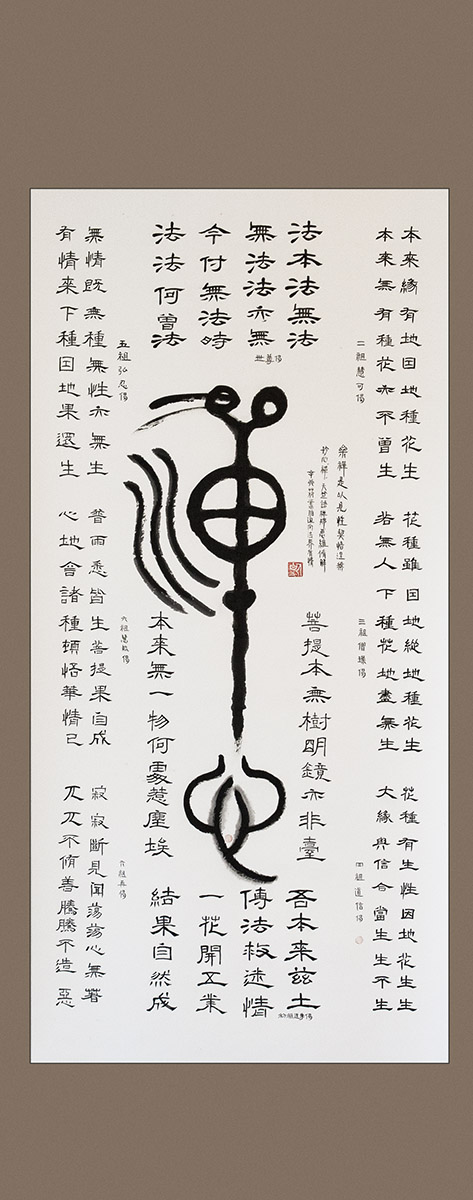

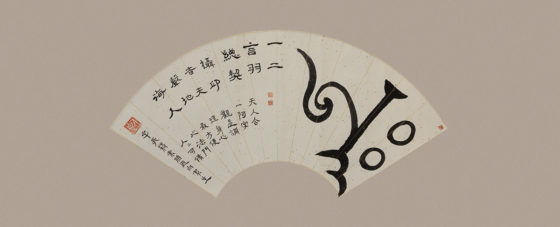

陈照心明 《敬先贤横渠四句》清华简

尺寸 :110cm x 96cm

钤印:照心明印(阳文)、照心明(阴文)

题跋:敬先贤横渠四句:为天地立心,为生民立命,为往圣继绝学,为万世开太平。

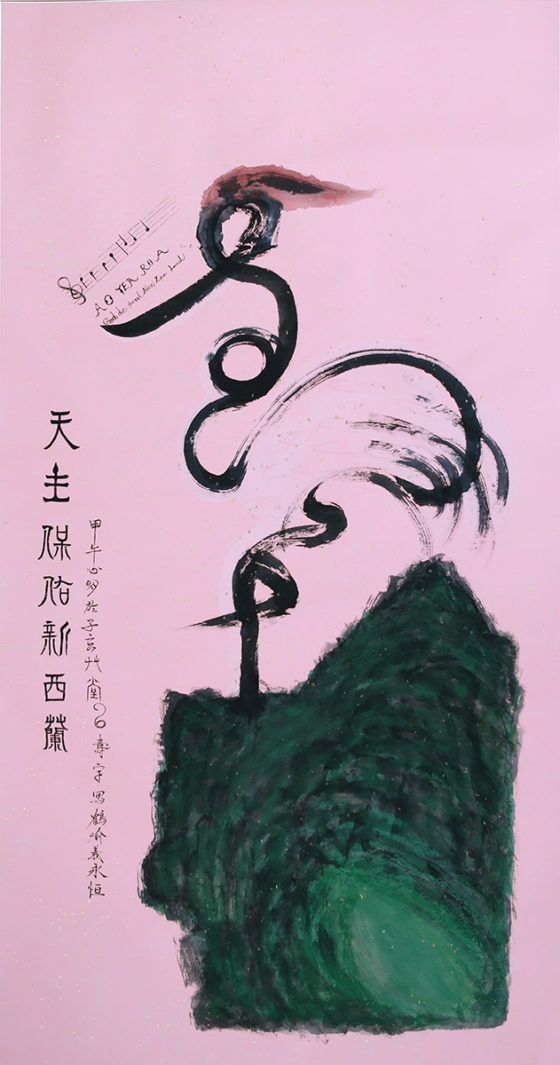

戊戌 新西兰陈照心明书。

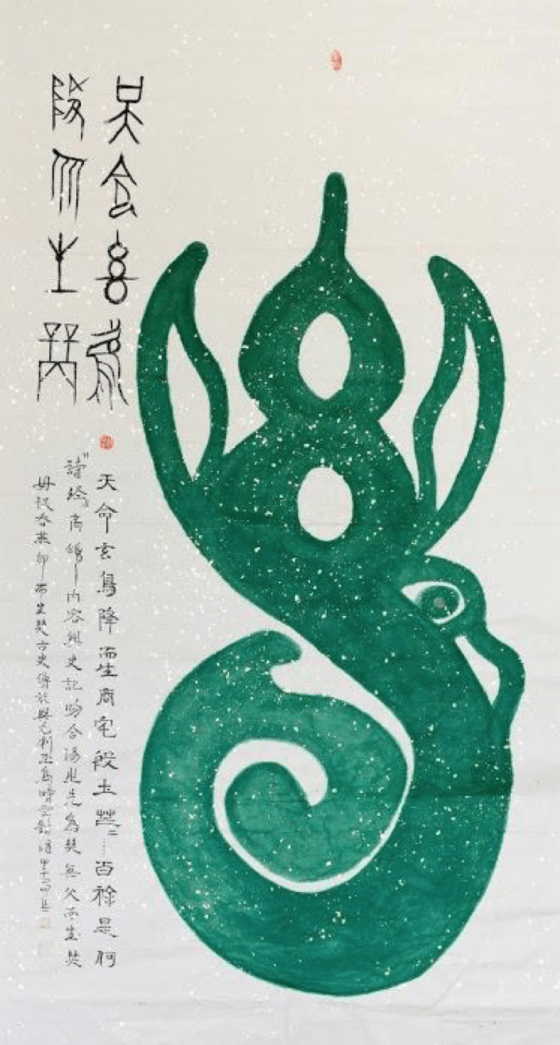

创作手记:一代思想家、教育家南怀瑾大德曾回忆:抗战期间,年轻的南老师去拜见一代鸿儒马一浮先生。那日,敲了好几次门,却没人答理。南老师心里很不高兴,对着马府门忍不住发泄道:“有什么了不起?你这位先生,还号召天下读书人为天地立心,为生民立命—-自己却那么骄傲——”嘀咕完,南老师正要离开,突然 马府中门大开,马先生与他的弟子们列队相迎,南老师的心怦怦直跳,说时迟那时快,赶紧跪拜向马大儒致敬! 心明创作这幅作品时,每想到这些先贤的故事,颇为景仰。放眼当代青年,为国家民族利益而生的理想抱负、家国情怀还有吗?

中国书画艺术有别于西方艺术,不仅仅是艺术的材质和技巧、审美的情趣和经验之不同, 更重要的是中国文人艺术家有一份与生俱来的“道统”,那就是 “成教化 ,助人伦”(唐-张彦远)。书法艺术自古既能直指人心,又能使光彩玄圣 。但人的才智有平庸峻拔之分。

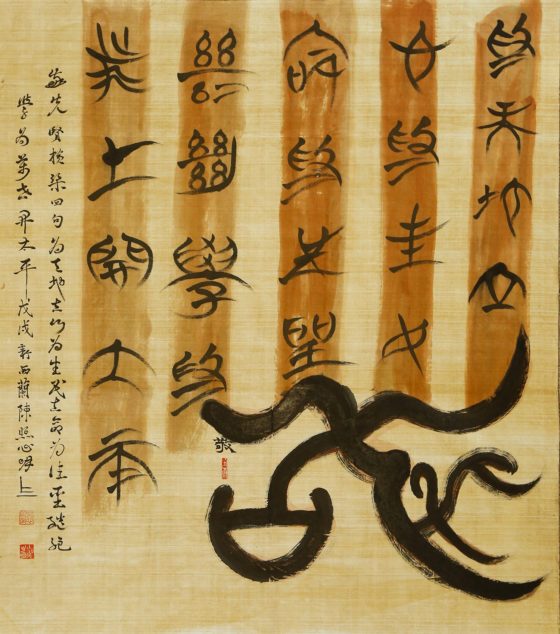

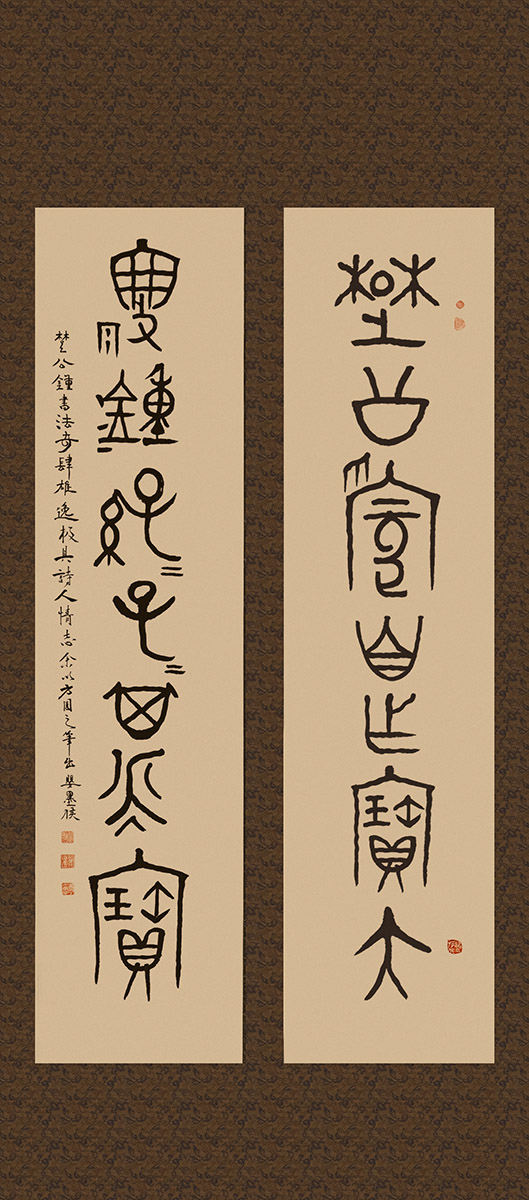

学识有深浅之别。心明在构思此作品时, 耳边有一个声音在问:“你的艺术穿透力是什么?”与其人人用篆、隶、真、行、草写“横渠四句”不如回到最古朴的战国简帛书体。近年恰逢授弟子们“清华简”,脑海呈现一种古书的情景,于是 铺纸濡墨 ,挥运之时,让书法三变其气:

一 是书 画同体, 在简书中画“出土竹简的形貌”, 先给读者注入怀古探胜之气, 以祛苍白说教的“病气”;

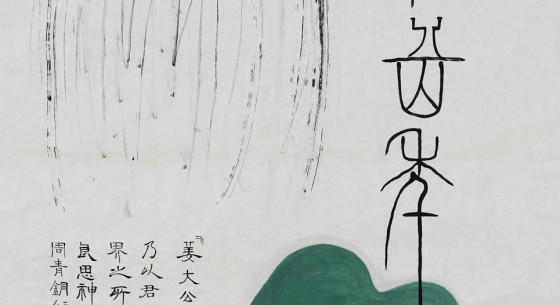

二是在右下角以草篆 书“敬 ”字, 与读者交照出温温其恭之气,以祛轻狂不俭之“俗气”;

三是题跋以晋人之书风,与读者交汇出“磊落”之气,以祛追名逐利之“鬼气”。

如上所述,在整幅作品,三变其气,锋发而韵流,直指人心的艺术穿透力,没点“血气” 之手 又岂能胜任?

原载陈照心明《心明书学大脚印2印》

Title: Chen Zhaoxinming’s “Reverence for the Four Phrases of Hengqu” – Tsinghua Bamboo Slips

Dimensions: 110cm x 96cm

Seals: Zhaoxinming’s Seal (in relief), Zhaoxinming (in intaglio)

Colophon: Reverence for the ancient sages and their Four Phrases of Heng Qu:

- Establish a heart for heaven and earth.

- Set life’s purpose for the people.

- Continue the lost teachings of past sages.

- Initiate a peaceful era for all generations to come.

2018, in New Zealand by Chen Zhaoxinming.

Creation Notes: Master Nan Huaijin, a thinker and educator of his generation, once recalled: During the Anti-Japanese War, the then young master Nan visited the great scholar, Mr. Ma Yifu. That day, after knocking several times without a response, Nan felt frustrated. He couldn’t help but vent his feelings towards the door of the Ma residence: “What’s so great about him? This gentleman calls upon scholars everywhere to ‘establish a heart for heaven and earth, and set life’s purpose for the people’ – yet he’s so arrogant…” Just as he finished murmuring and was about to leave, the central door of the Ma residence swung open, with Mr. Ma and his disciples lined up to greet him. Nan was startled and quickly knelt to pay his respects. As I created this piece, I felt great admiration every time I thought of these stories about the ancient sages. I wonder, do contemporary youth still possess such ideals and affections for their nation?

Chinese calligraphy and painting differ from Western art. It’s not just about differences in materials, techniques, aesthetics, or experiences. More importantly, Chinese literati artists possess an inherent “orthodoxy” of “moral cultivation and transformation, assist in human relations” (Tang Dynasty – Zhang Yanyuan). Calligraphy can directly touch human hearts and can also make it mysterious and sacred. However, people’s talents differ, as do their depths of knowledge. As I conceived this work, a voice in my ear asked, “What’s the penetrative power of your art?” Instead of everyone writing the “Four Phrases of Heng Qu” in various scripts, why not return to the most ancient script from the Warring States Period? Recently, while teaching my students the “Tsinghua Bamboo Slips”, an image of ancient texts appeared in my mind. Thus, I spread out the paper and dipped my brush in ink, as I moved with flowing strokes, I allowed my calligraphy to undergo three transformative energies (chi):

- First, calligraphy and painting are of the same essence. By depicting the unearthed bamboo slips, imbues the reader with a sense of antiquity and the thrill of exploration, dispelling the “sickly air (chi)” of bland preachiness.

- Second, in the right bottom corner, I wrote the character “敬” (respect) using a cursive script, resonating with the reader and conveying a gentle reverence.

(conveying a humble attitude to the reader, ) countering any sense of arrogance or frivolity, the “air (chi) of vulgarity.”

- Using the script style of the Jin Dynasty for the colophon, conveying a straightforward and unpretentious demeanour, and dispelling any greed for fame or profit, the “ghostly air (chi)”

As mentioned, throughout the artwork, these three energies (chi) shift, sharp and rhythmic, directly touch the human heart. How could a hand without a hint of “vitality” (“vigour”)or “spirit” be fit for the task?

Originally published in Xinming’s Footprint in Calligraphy—2nd Edition, Chen Zhaoxinming

Translated by Sylvia Yang