escort şişli nişantaşı escort bayan mecidiyeköy escort hulya şişli escort duru mecidiyeköy escort meltem mecidiyeköy escort defne mecidiyeköy escort yaren mecidiyeköy escort deniz escort bayan mecidiyeköy escort ferda mecidiyeköy şişli escort pelin vip escort sınırsız escort grup escort mecidiyeköy escort sıla mecidiyeköy escort ezgi escort istanbul

Information

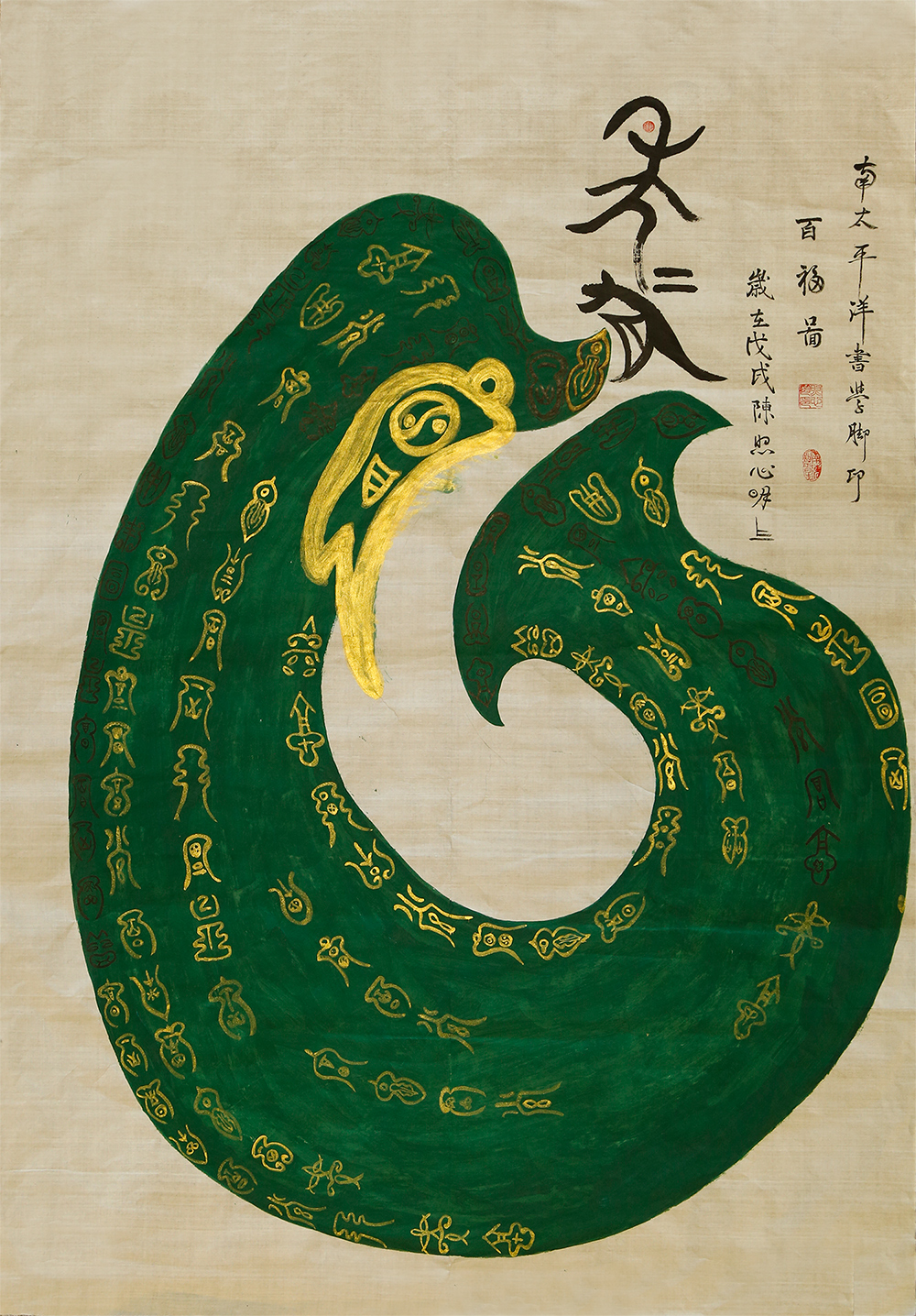

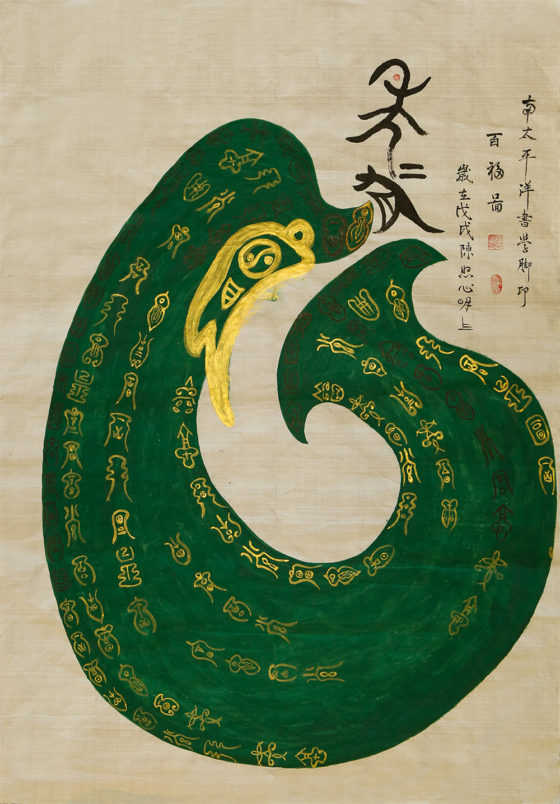

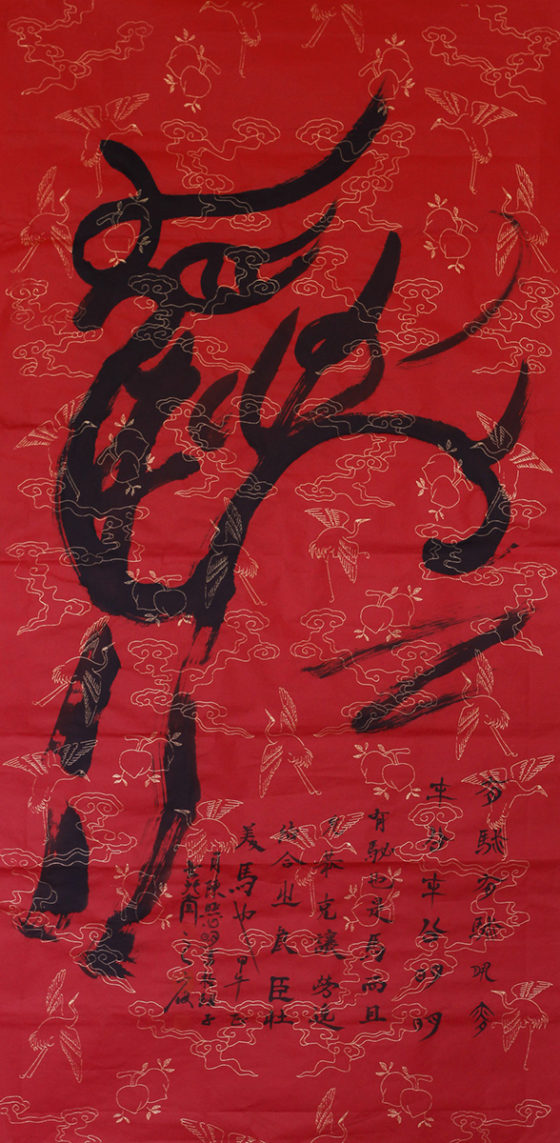

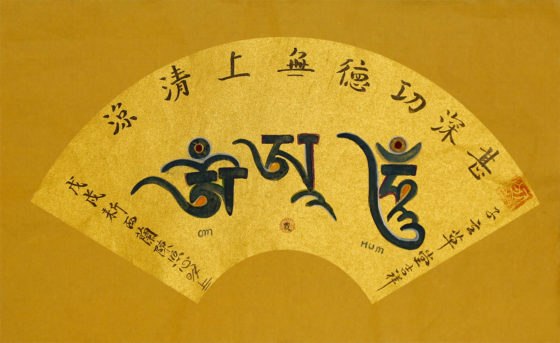

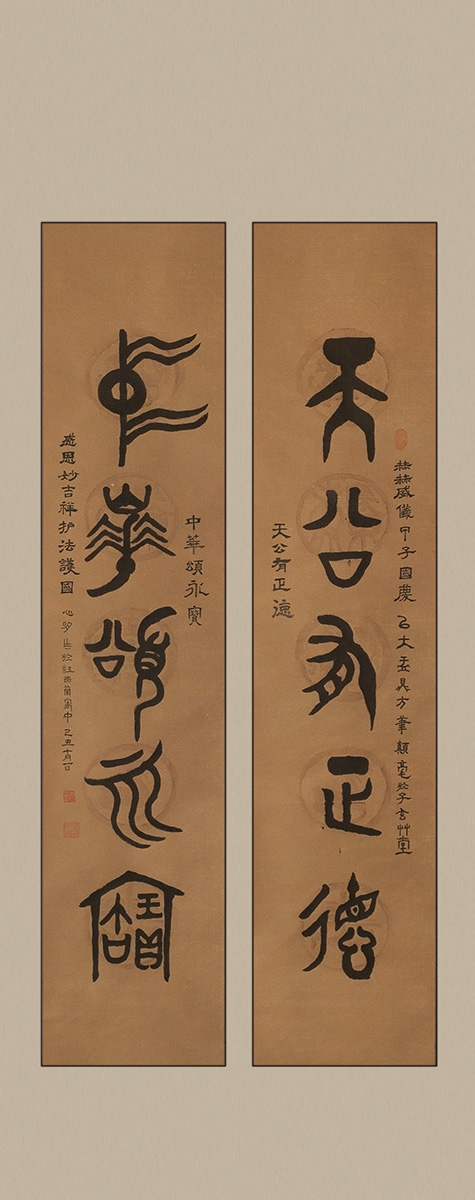

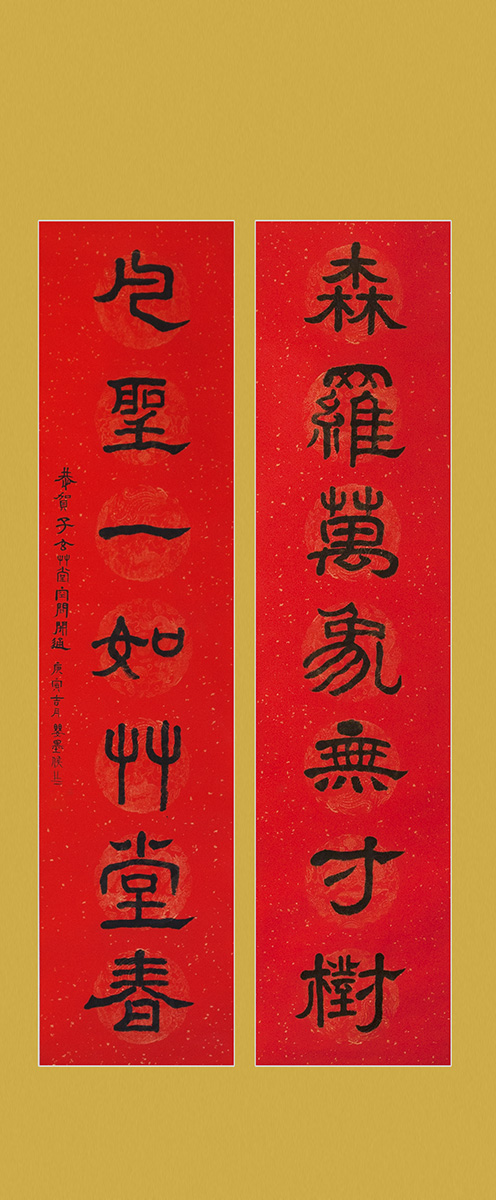

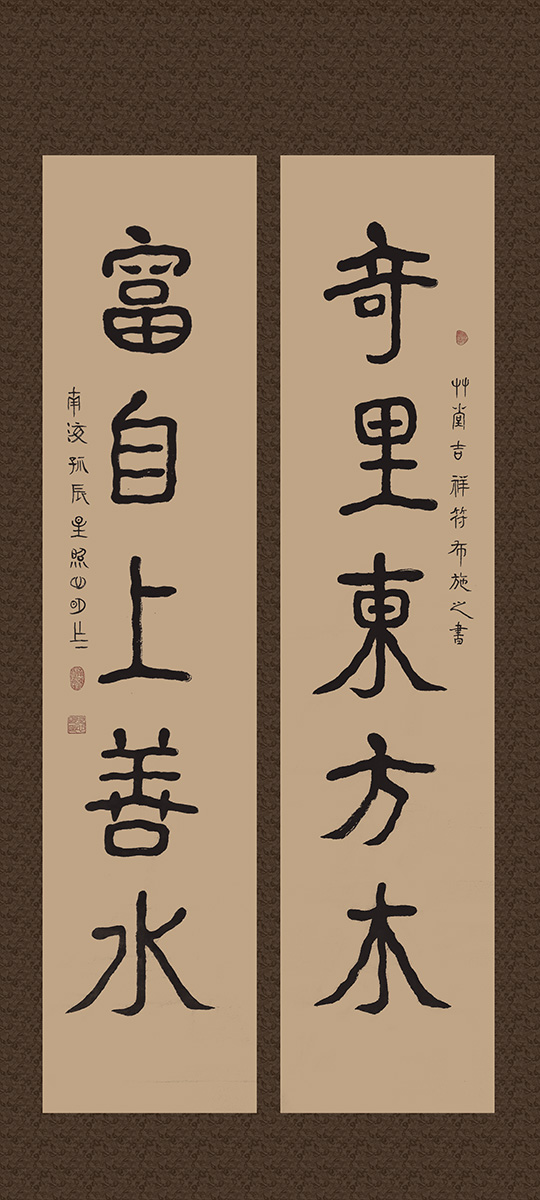

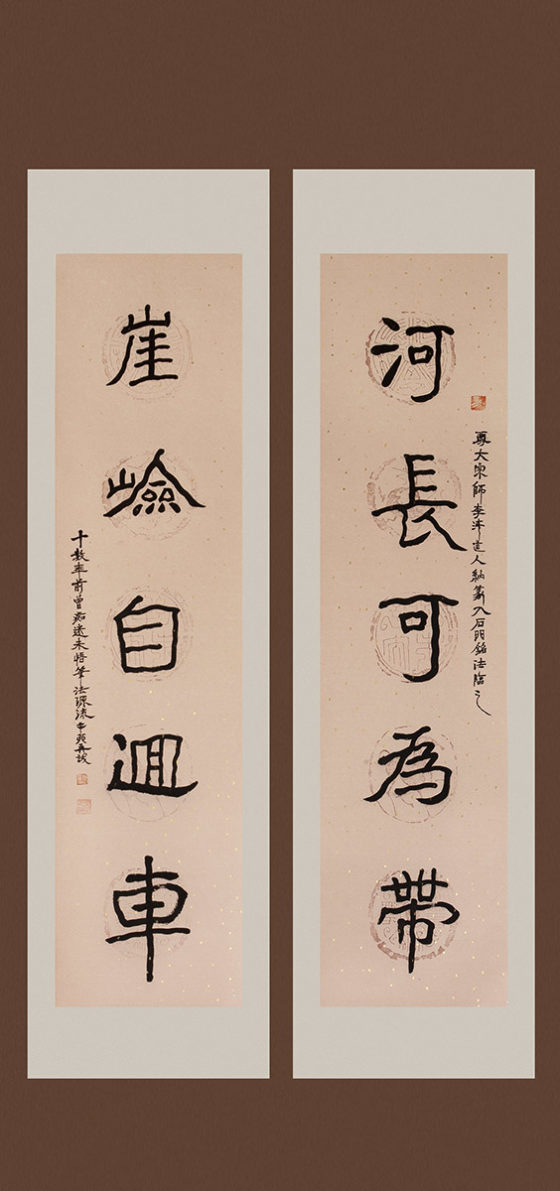

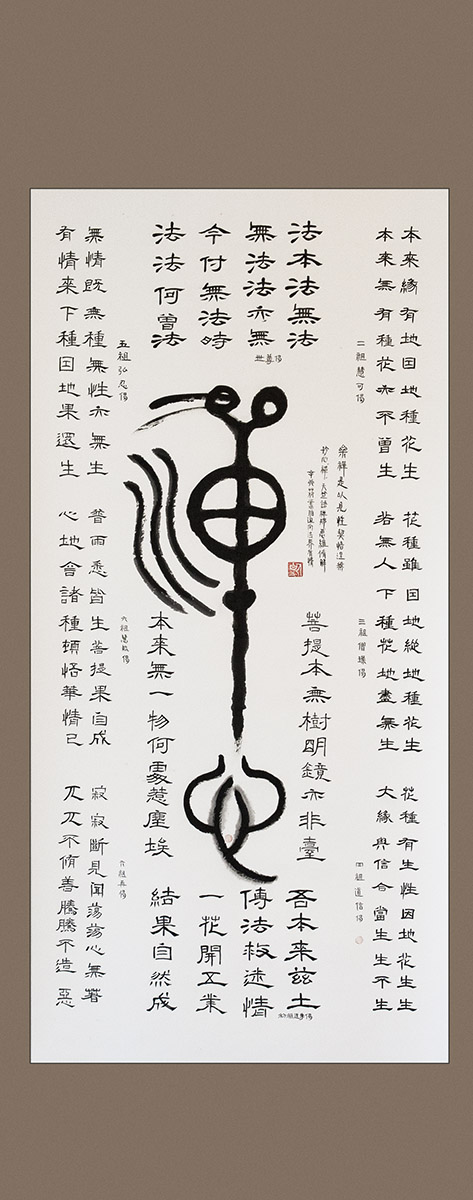

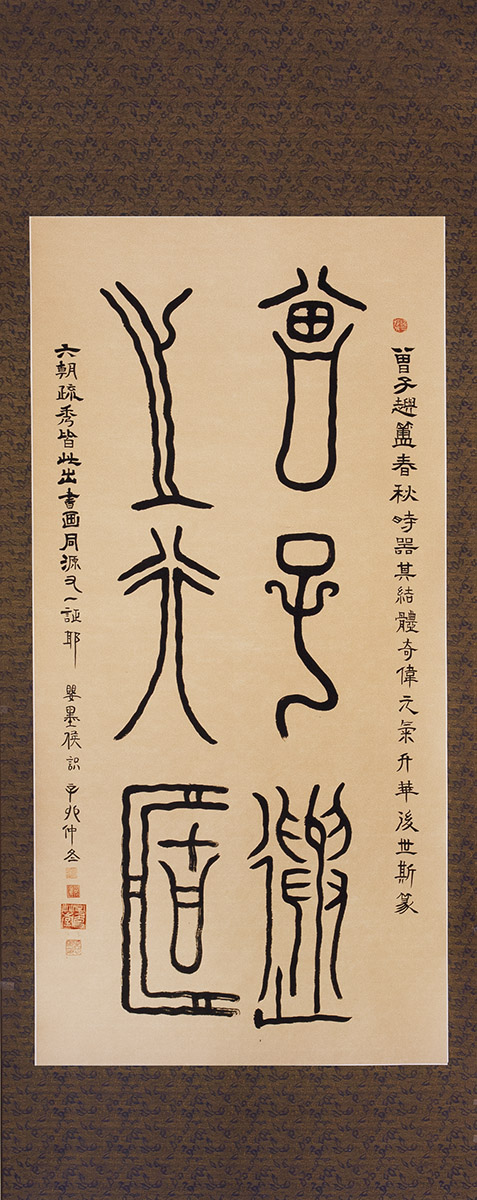

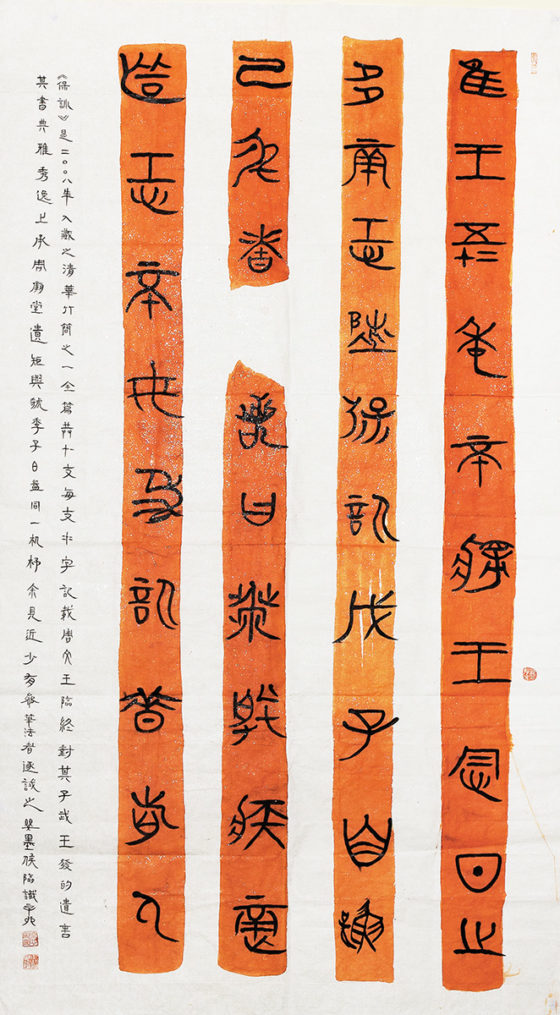

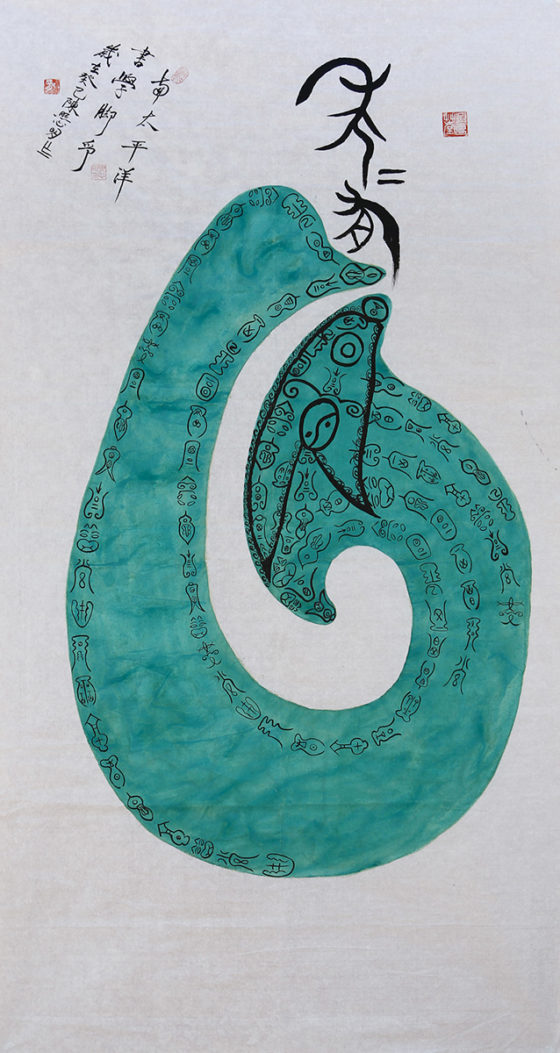

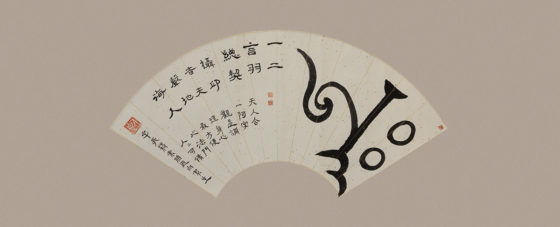

陈照心明 《南太平洋之百福图》 当代艺术

英译:Hei Matou (More than you wish)baifu painting

Hanging Scroll.

原载;陈照心明《心明书学大脚印—2印》

尺寸: 134cm x 96cm

钤印:照心明印;南海孤辰星;心明

题跋:南太平洋书学脚印之百福图。

岁在戊戌 陈照心明作。

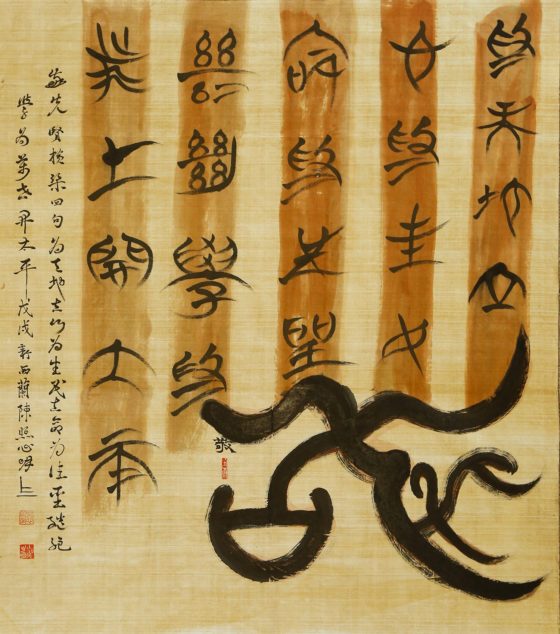

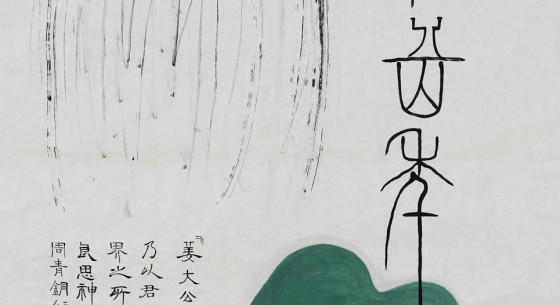

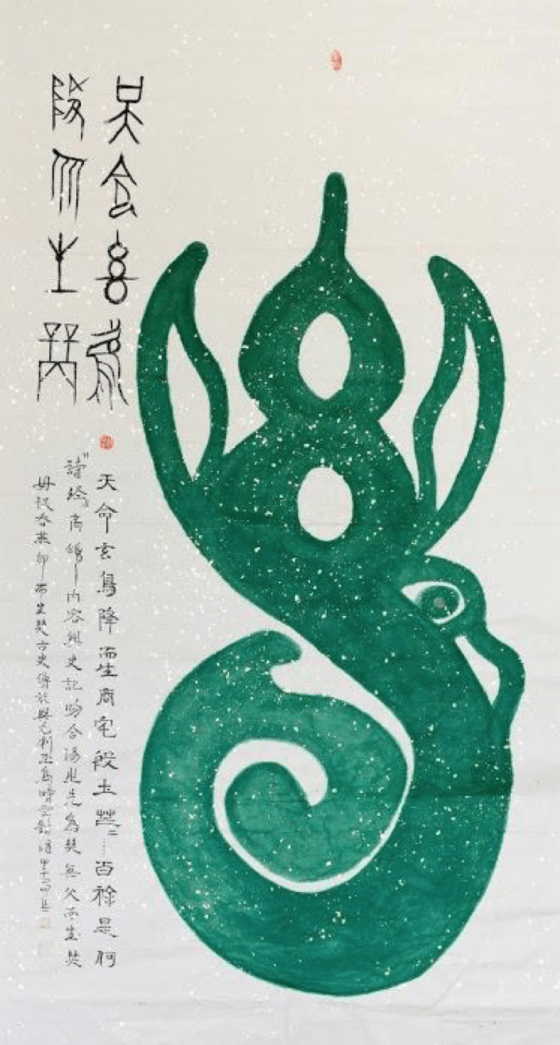

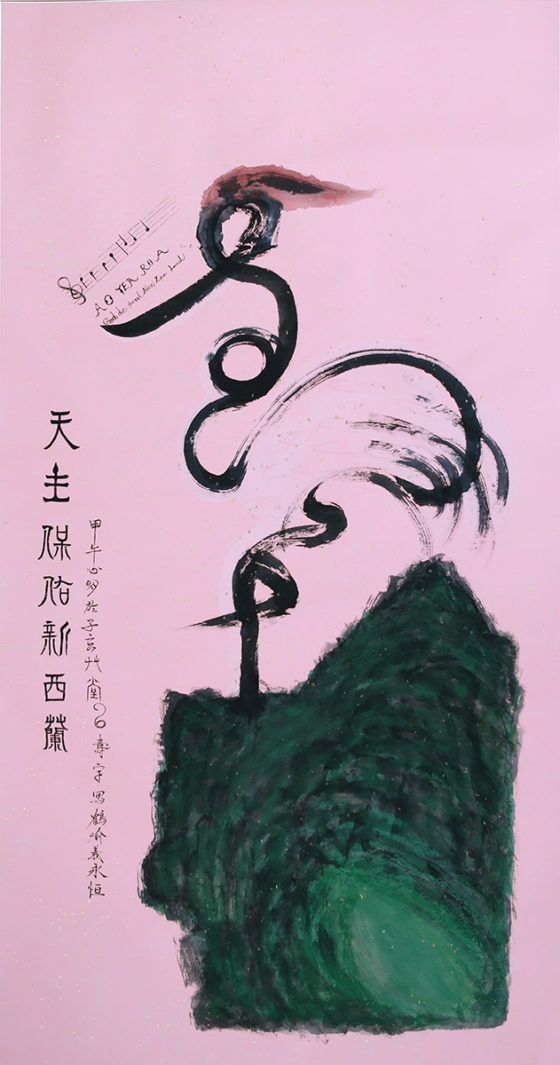

创作手记:不知什么时候开始有的人认为艺术终究是为富人服务的,于是所谓的当代艺术尽管技巧构思前卫,但缺乏艺术的精神灯塔,尽显功利主义的创作潮流。 以商品炒作火箭般的价格来衡量一幅作品的价值, 使民族艺术、精英艺术陷入空前的悲哀 。 心明认为艺 术不仅再现我们六根六尘所识,更重要的是展现民族的精神风貌: 唐代的山水画家多半描绘宏伟山水以表现堂堂大人相 。 而元代的画家则喜爱平远的山和绿竹寒泉,来表现遗世而独立的圣贤远奥韵致。作为二十一世纪 的艺术家,我们应该为子孙后代留下怎样的精神财富? 在研究中国吉祥符号与毛利文化符号过程中了解到毛利文化符号KORU(银蕨)是 象征 幸福、长寿和生命不息。Matou(鱼钩),则象征五谷丰登,幸福绵绵。谁说毛利没有文字,符号就是他们的文字,而且对宇宙万物吉祥气场曲线的感应特别强烈。如同中国传统文化领域中遍布的吉祥符号一样。,尤其书画同源的“百福图、百寿图”上至天子下及庶民,无不钟爱有加。既然两国文化如此的同明相照,于是心明尝试用100个符号“福”字写进毛利鱼钩符号里,既别开生面地打破中国传统“百福图“的程式,更为两国吉祥文化符号定百年之好。 还妙用钟鼎文《大盂鼎》书体在鱼钩口篆“年年有鱼(余),奇趣的鱼儿腾跃海波,寓意两国吉祥文化符号如胶似漆,天禄云集。 整幅作品虽在平面视觉空间,通过花青、赭石、丙烯黄和深蓝调出毛利文化“绿玉“典雅”的韵味。为能提高作品调子,特意用墨与金墨书百福字, 让观众将自己对美好事物的直觉,升华出一种无穷的意蕴。也就是一种“富贵气”场的螺旋情感和价值观。倘若全部字符用黑色,固然有“冷逸”之美,但“福”乃大公无私的天地所赐。情畅而壮丽的金墨,让读者心灵沉浸在艺术想象与憧憬之中。

Title: Hei Matou (“More than you wish”) Baifu Painting of the South Pacific

Art Form: Contemporary Art

Format: Hanging Scroll

Originally published in Xinming’s Footprint in Calligraphy—2nd Edition by Chen Zhaoxinming.

Dimensions: 134cm x 96cm

Seals: Zhaoxinming seal; Lone Star of the South Sea; Xinming

Colophon: “Baifu Painting” — Footprint of South Pacific Calligraphy.

Created in the year of Earth Dog, by Chen Zhaoxinming.

Creative Notes: Somewhere along the line, some began to believe that art ultimately serves the wealthy. As a result, contemporary art, though technically advanced and avant-garde in concept, lacks the guiding spirit of true art, and is dominated by utilitarian trends. Judging the value of a piece based on its skyrocketing market price has led to a profound sadness in both national and elite art forms.

Xinming believes that art not only represents what our six senses perceive but more importantly, showcases the spiritual demeanor of a nation. Landscape painters from the Tang Dynasty often portrayed grand landscapes to express the majestic demeanour of great individuals. Yet, artists from the Yuan Dynasty preferred serene mountains, green bamboo and icy springs, symbolising the subtle charm of reclusive sages. As 21st-century artists, what kind of spiritual wealth should we leave for future generations?

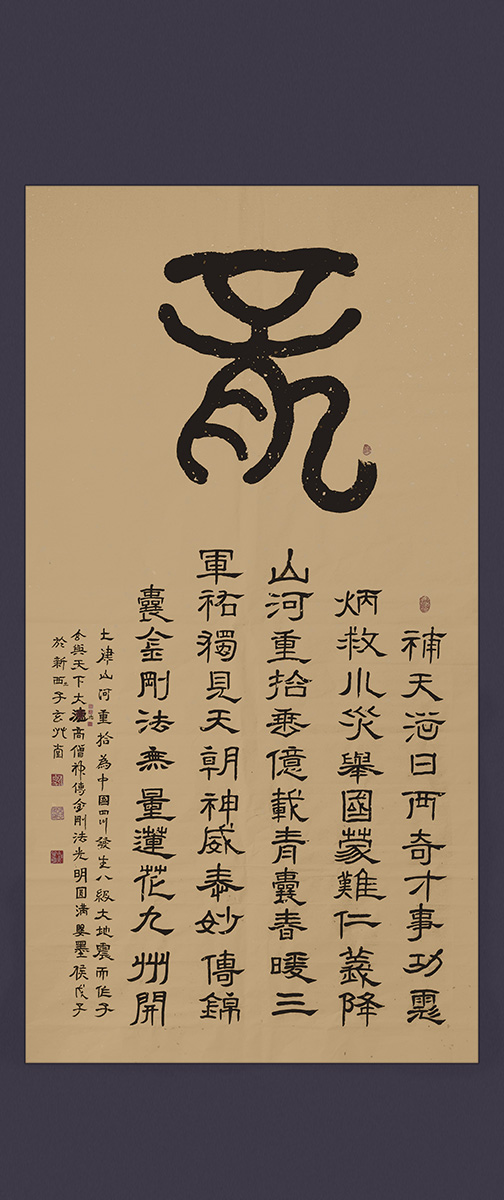

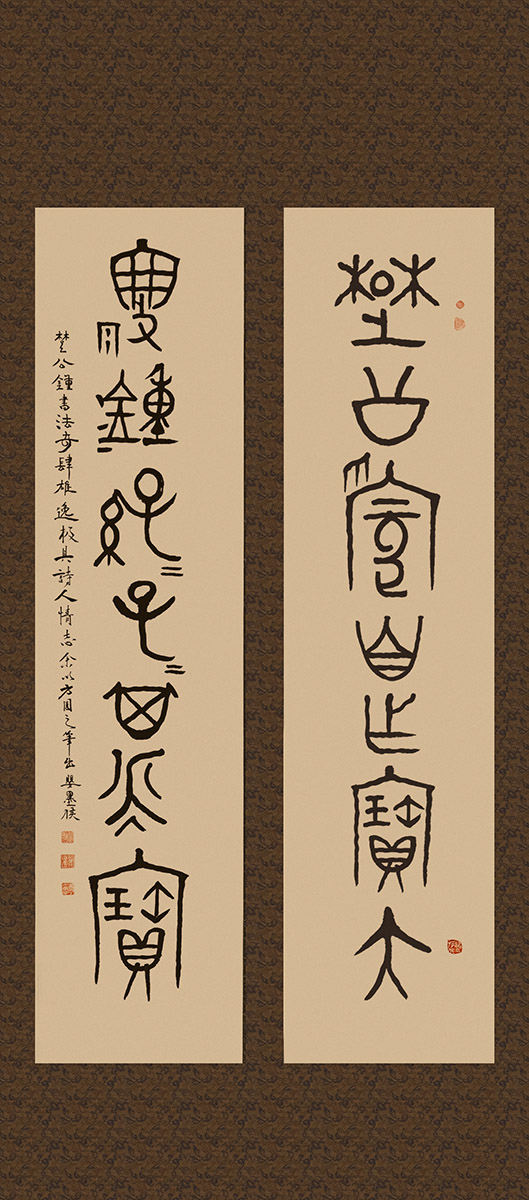

Through the study of Chinese auspicious symbols and Māori cultural symbols, I discovered that the Māori symbol KORU (silver fern) represents happiness, longevity, and the perseverance of life. Matou (fishhook) symbolises bountiful harvest and continuous happiness. Who says the Māori lack written language? Symbols are their words, and they are particularly sensitive to the auspicious energies of the universe. Just as in Chinese culture, where auspicious symbols are everywhere, especially in the synonymous calligraphy and paintings of “Hundred Blessings” and “Hundred Longevity”, they are loved by both the emperor and the common people. Given the similarities between the two cultures, Xinming attempted to embed 100 “福” (blessing) characters within the Māori fishhook symbol, not only innovatively breaking the traditional Chinese “Hundred Blessings” format but also forming a century-long bond between the auspicious symbols of the two nations. Ingeniously, she used the script of the Da Yu Ding (大盂鼎) to inscribe “年年有鱼 (fish every year)” on the fishhook, symbolising the close bond and abundant fortune of the two cultures.

Although the artwork exists in a two-dimensional space, through the use of azure, ochre, acrylic yellow, and deep blue, it captures the elegant charm of the Māori culture’s “pounamu”. To enhance the work’s tone, special black and gold ink was used for the blessing characters, allowing the audience to elevate their intuition for beautiful things, giving rise to endless implications, a kind of “wealthy aura” of spiralling emotions and values. If all characters were in black, while it would present a “cold elegance”, “福” (blessing) is a selfless gift from the universe. The bright and magnificent gold ink immerses the reader in the realm of artistic imagination and aspiration.

1.Da Yu Ding (大盂鼎): A “Ding” (鼎) is an ancient Chinese ritual bronze vessel with three or four legs. It was used for cooking, storage, and ritual offerings to the ancestors during the Shang and Zhou dynasties. Over time, the “Ding” also became a symbol of power and authority in ancient China. Its design and inscriptions reflect the artistry, culture, and social structures of the periods in which they were made. The Da Yu Ding is the largest known piece among the ancient Chinese ritual bronze vessels. Dated to the late Shang dynasty (13th century BC), it is renowned for its intricate inscriptions and is considered an important artifact in the study of ancient Chinese history and bronze casting. The inscriptions on the vessel pay tribute to the achievements and virtues of Yu’s ancestors, serving as a significant historical document. The Da Yu Ding is a testament to the craftsmanship and cultural importance of ritual vessels in ancient China.

Translated by Sylvia Yang